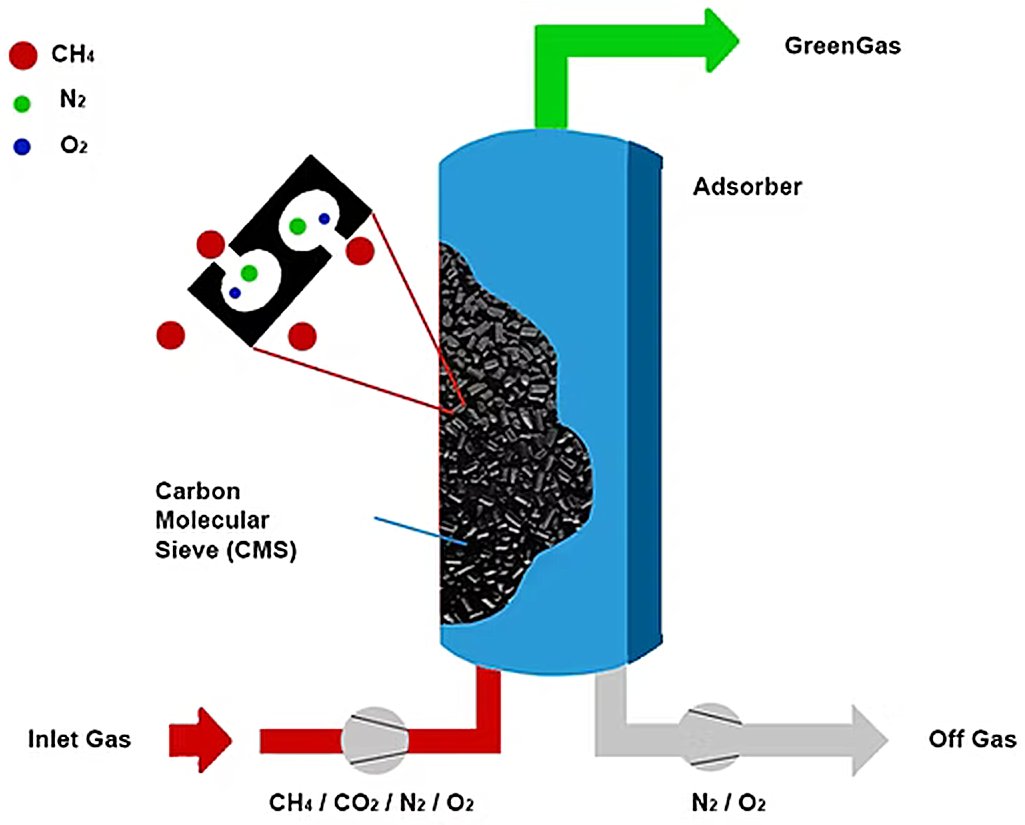

Regenerative adsorption systems use specialized adsorbent materials that can be repeatedly cycled between adsorption and desorption states, eliminating the need for continuous adsorbent replacement and enabling economically viable continuous operation. These technologies separate gas components by exploiting the selective affinity of adsorbent materials for specific molecules under varying operating conditions, with applications spanning hydrogen purification, air separation, natural gas treatment, and industrial gas production.

Fundamentals of Adsorption

Adsorption is a surface phenomenon where atoms, ions, or molecules from a gas, liquid, or dissolved solid adhere to the surface of an adsorbent material without penetrating into its bulk structure. The process relies on physical adsorption (physisorption) using specialized materials that feature enormous internal surface areas up to 1,000 m²/g and precisely controlled pore structures.

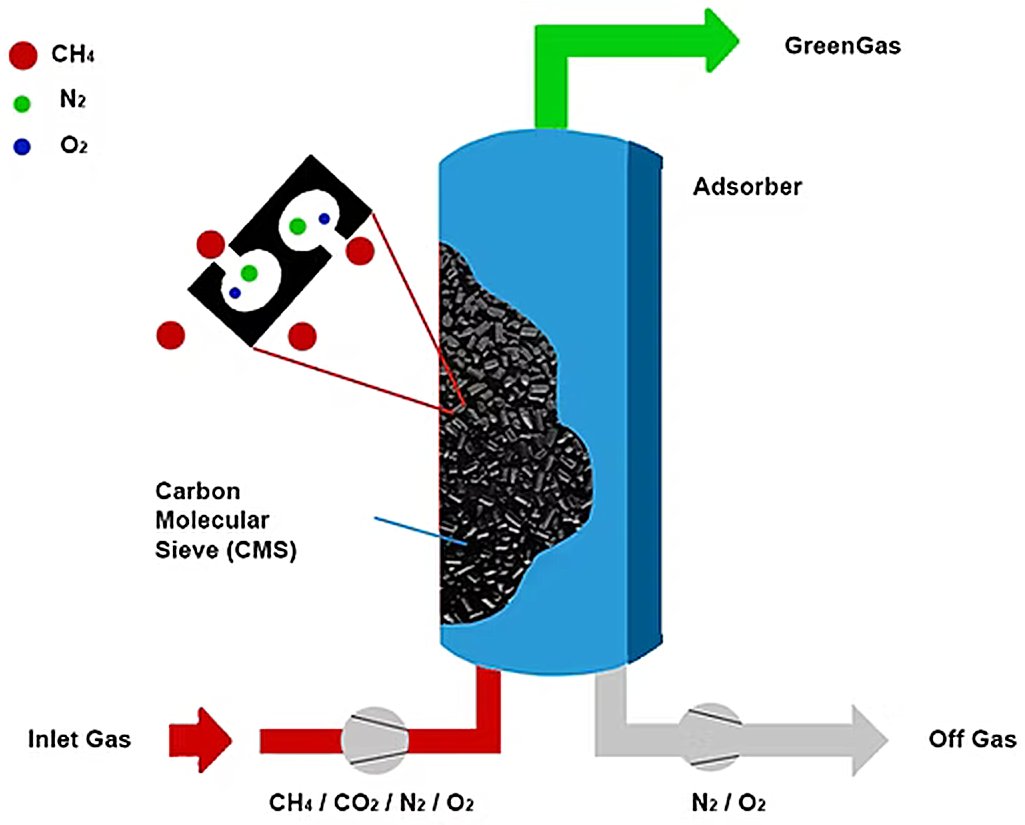

Figure 1 — PSA selective gas molecules adsorption principle [1]

Adsorbent Materials

The major types of commercial adsorbents include activated carbon, carbon molecular sieves, zeolite molecular sieves, silica gel, activated alumina, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Each material exhibits distinct characteristics in terms of porosity, pore structure, and surface chemistry.

Figure 2 — Adsorbents [10]

- Zeolite molecular sieves: Crystalline aluminosilicates with uniform pore sizes ranging from 3-10 Å, offering high selectivity for polar molecules including water, CO2, H2S, and methanol

- Carbon molecular sieves: Used primarily for nitrogen/oxygen separation in air, with kinetic selectivity based on molecular size differences

- Activated carbon: Amorphous material with pore sizes averaging 10-500 Å, effective for removing organic compounds and non-polar molecules

- Silica gel and activated alumina: Amorphous materials with average pore sizes around 50 Å, commonly used for dehydration applications

Separation Mechanisms

Adsorptive separations exploit dissimilar physical properties of gas components including kinetic diameter (molecular size), polarity, and polarizability. The choice of adsorbent in terms of capacity and selectivity is critical for effective process design. Separation selectivity is defined as:

S = (xA / yA) / (xB / yB)

where xi represents the adsorbed phase mole fraction and yi represents the gas phase mole fraction.

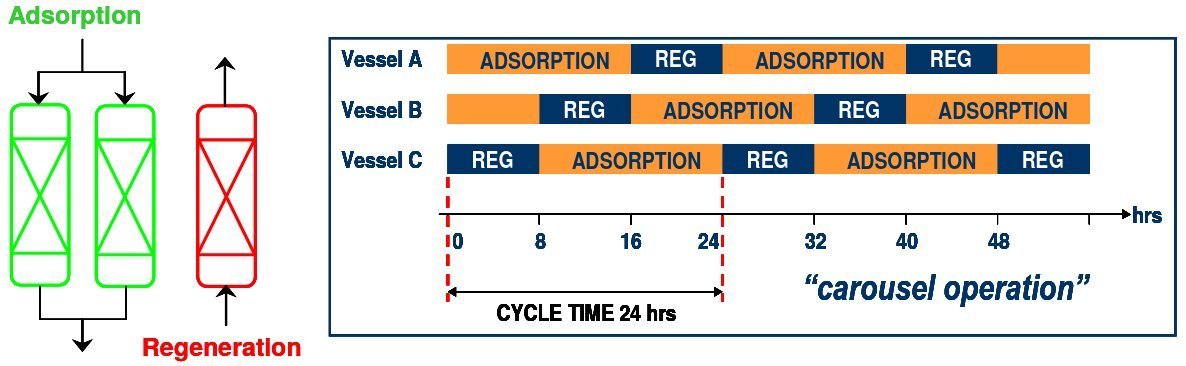

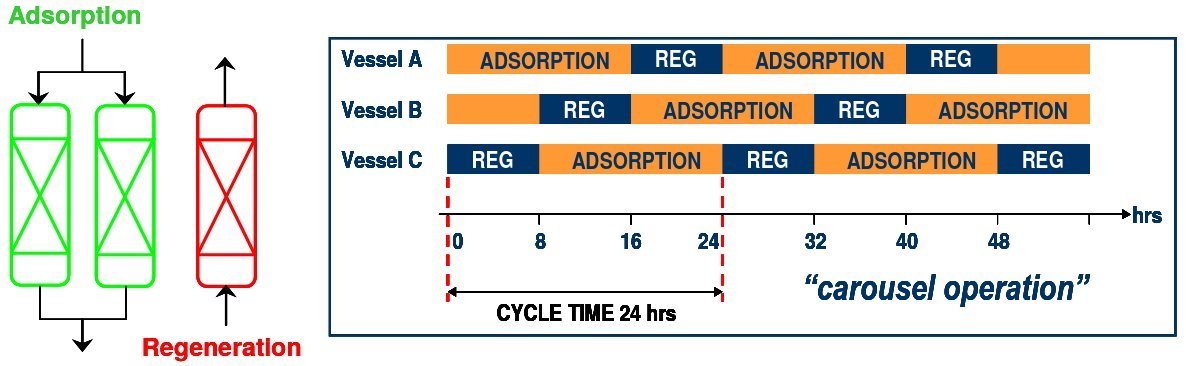

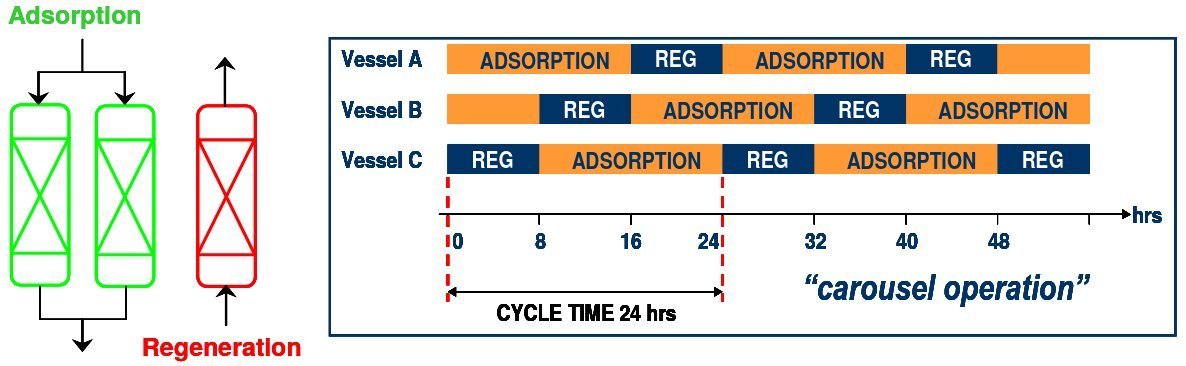

Figure 3 — Example of a “2+1” TSA for natural gas dehydration and purification using molecular sieves with 16 hours adsorption and 8 hours regeneration [16]

Regeneration reverses the adsorption process by changing equilibrium conditions—either temperature (TSA), pressure (PSA, VPSA), or both—causing adsorbed molecules to desorb from active sites and restoring the adsorbent's original capacity. This regenerative capability transforms what would be a batch process into a continuous, economically sustainable operation.

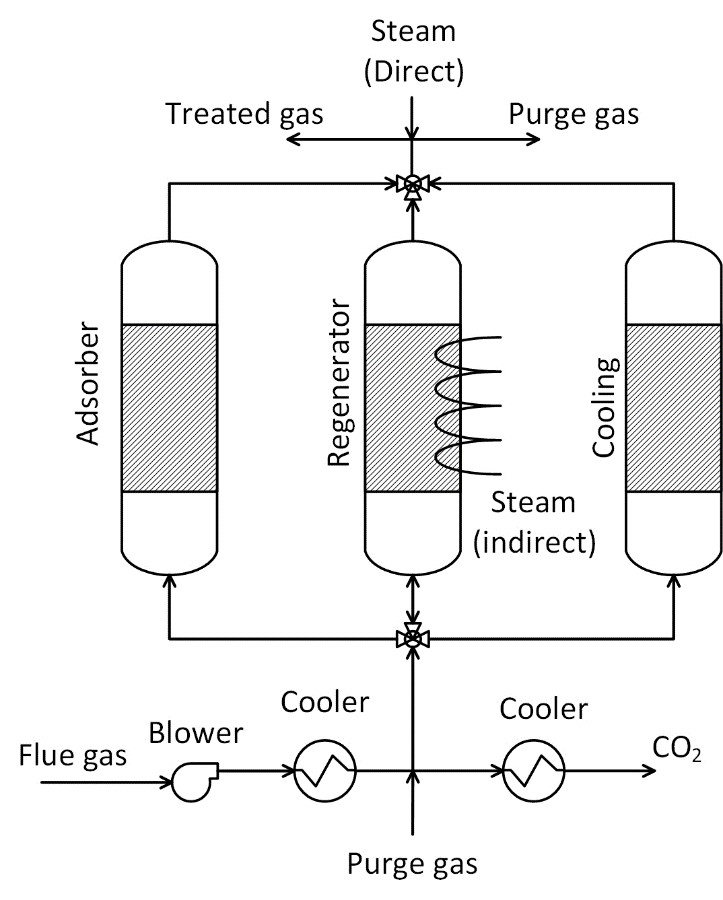

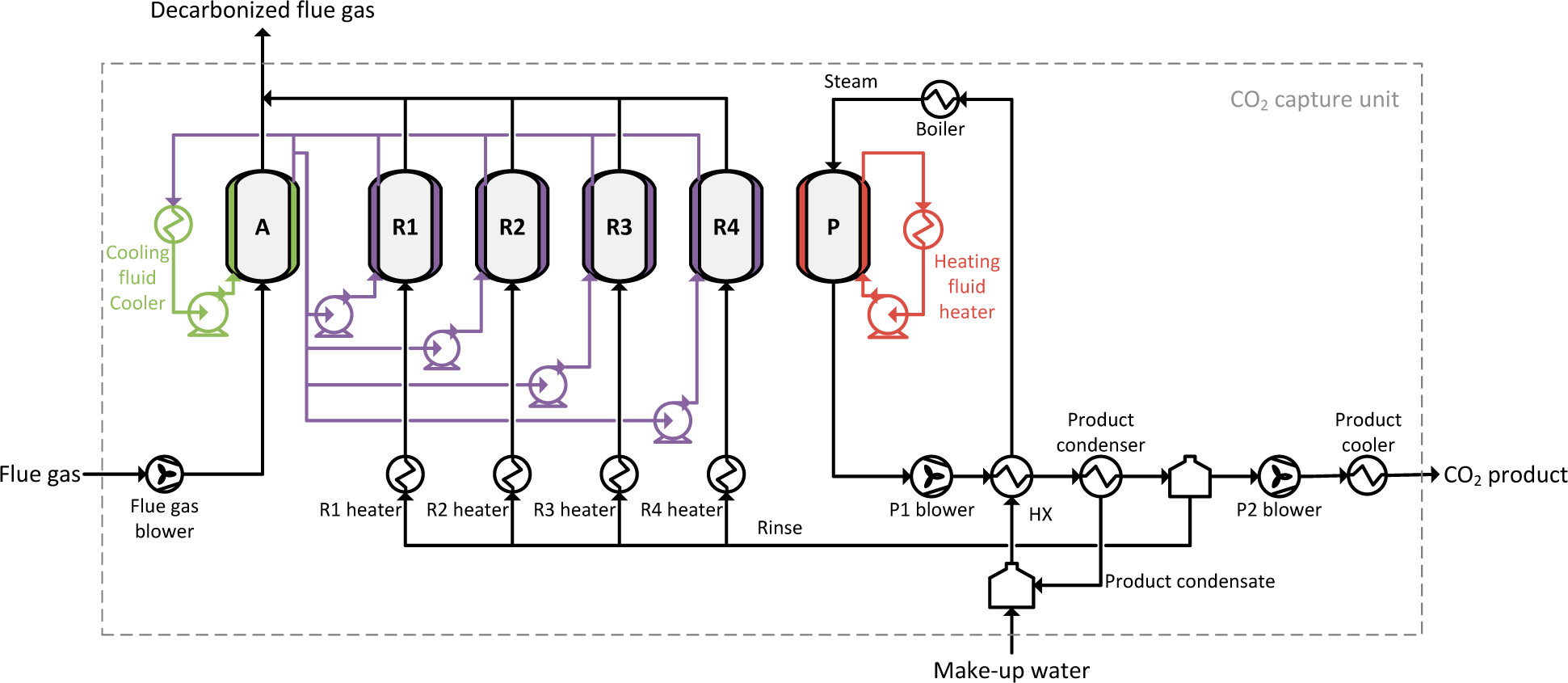

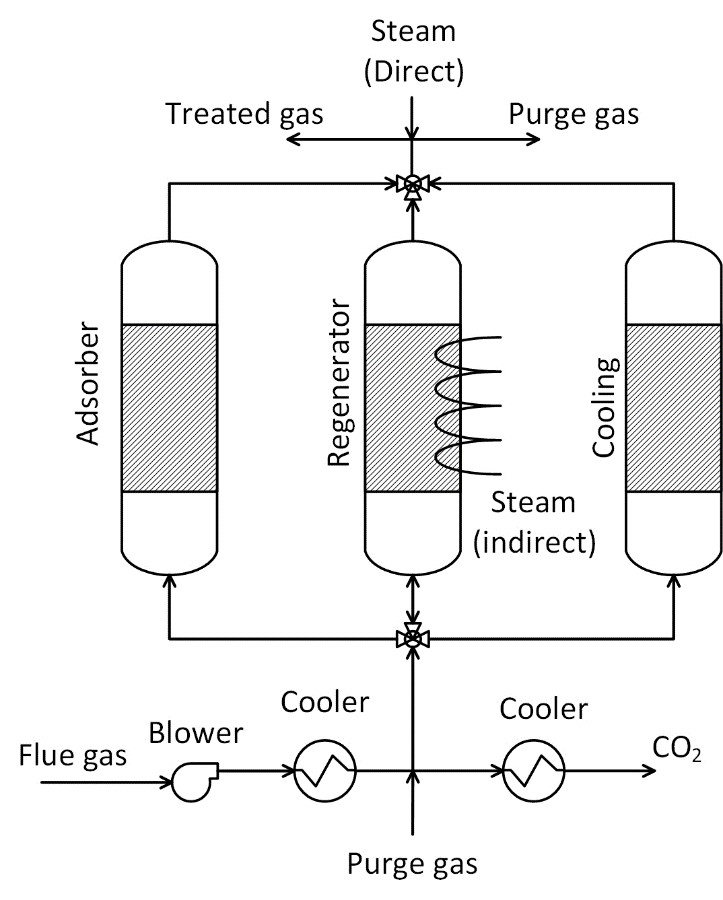

Temperature Swing Adsorption (TSA)

TSA exploits adsorbents with high adsorption rates at low temperatures and regenerates them by applying elevated temperatures. The typical cycle consists of adsorption at ambient pressure and temperature, countercurrent regeneration at higher temperature, and cooling to prepare for the next adsorption cycle.

Figure 4 — Temperature swing adsorption process [2]

Regeneration Methods

TSA regeneration is accomplished through two primary heating approaches:

- Direct heating: Low or medium-pressure steam fed directly into the adsorbent bed

- Indirect heating: Heating medium (steam or thermal fluid) circulated through heat exchanger tubes embedded within the adsorbent bed

Indirect heating reduces cycle time, increases productivity, and enables heat integration in multi-bed configurations by recirculating thermal fluid between adsorbers. Regeneration temperatures typically range from 130-150°C or higher depending on adsorbent and application.

Indirect heating reduces cycle time, increases productivity, and enables heat integration in multi-bed configurations by recirculating thermal fluid between adsorbers. Regeneration temperatures typically range from 130-150°C or higher depending on adsorbent and application.?

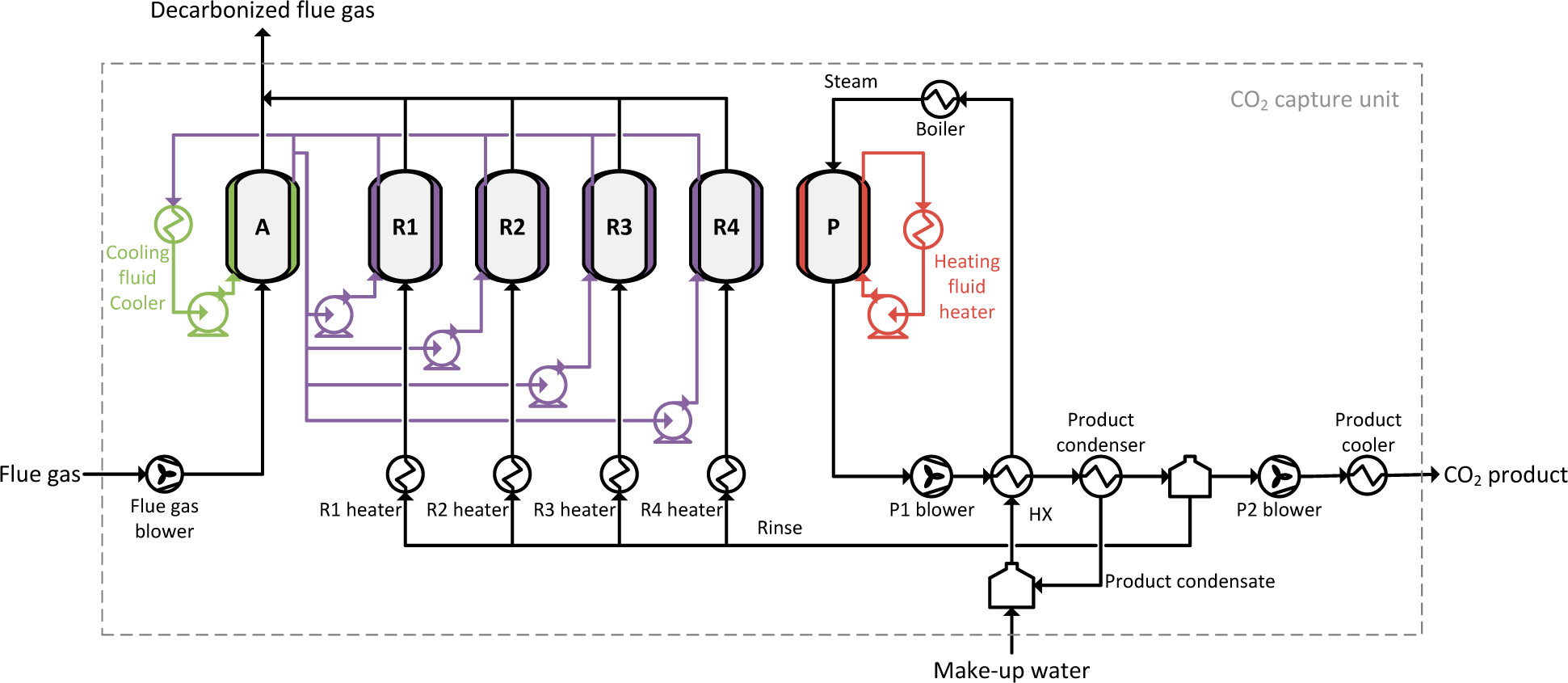

Process Configuration

TSA systems employ multiple beds operating in parallel to maintain continuous operation while individual beds undergo regeneration. The longer cycle times required to heat and cool adsorbent material—typically ranging from minutes to hours—necessitate larger bed volumes compared to pressure-based systems.

Figure 6 — Simplified TSA process flow diagram for CO2 removal from a coal plant flue gas based on steam stripping in combination with structured carbon adsorbents [16]

Applications

- Natural gas dehydration: Removing water vapor using molecular sieves, activated alumina, or silica gel to prevent hydrate formation and meet pipeline specifications

- Air drying: Producing instrument-quality dry air for pneumatic systems, analytical equipment, and process applications

- Gas purification: Removing CO2, CO, and water from hydrogen production, petrochemical processes, and industrial gas streams

- Volatile organic compound (VOC) removal: Activated carbon systems for solvent recovery and air pollution control

Advantages and Limitations

TSA allows maximum utilization of adsorbent capacity because high-temperature regeneration most effectively removes adsorbed contaminants. The technology is uniquely qualified for complete contaminant removal in certain applications. However, longer cycle times result in higher capital costs due to larger bed requirements and increased energy consumption for heating and cooling cycles.

Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA)

PSA utilizes adsorbents with high adsorption rates at elevated pressure and regenerates them by reducing pressure. The technology has become the most widely deployed adsorption-based separation process at industrial scale.

Figure 6 — Pressure swing adsorption process [3]

Process Cycle Steps

A basic two-bed PSA configuration operates with four fundamental steps, with beds operating 180°C out of phase:

- Pressurization: Feed gas pressurizes the bed to operating pressure

- Adsorption: At high pressure (typically >8 bar), target components selectively adsorb while product gas exits

- Blowdown/Depressurization: Pressure reduces to atmospheric or lower, initiating desorption

- Purge: A portion of purified product gas flows countercurrently through the bed to complete regeneration

Advanced multi-bed systems (4-16 beds) incorporate additional steps including multiple pressure equalization stages to improve energy recovery and product yield. These configurations systematically transfer gas between beds at intermediate pressures to reduce compression energy and increase recovery.

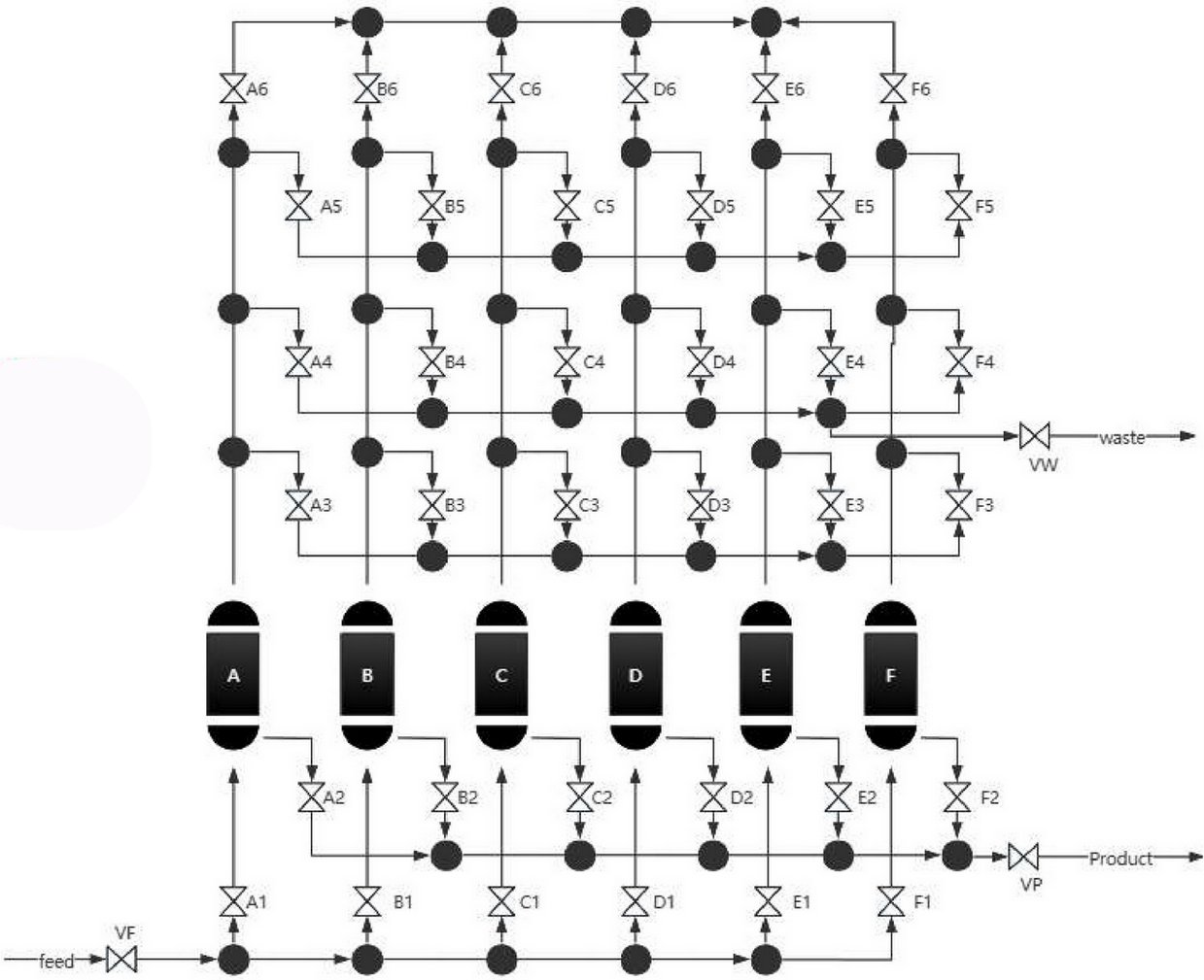

Multi-Bed Configurations

Commercial PSA processes employ multiple beds operating simultaneously, with each bed undergoing cycle steps in sequence. Common configurations include:

- Two-bed systems: Simplest configuration for continuous operation with basic four-step cycles

- Three-bed systems: Enable continuous feed operation with shorter beds and optimized pressure ratios

- Four to six-bed systems: Incorporate pressure equalization steps to improve energy efficiency and product recovery

- Ten to sixteen-bed systems: Complex configurations with multiple pressure equalization steps for maximum hydrogen recovery from refinery off-gases

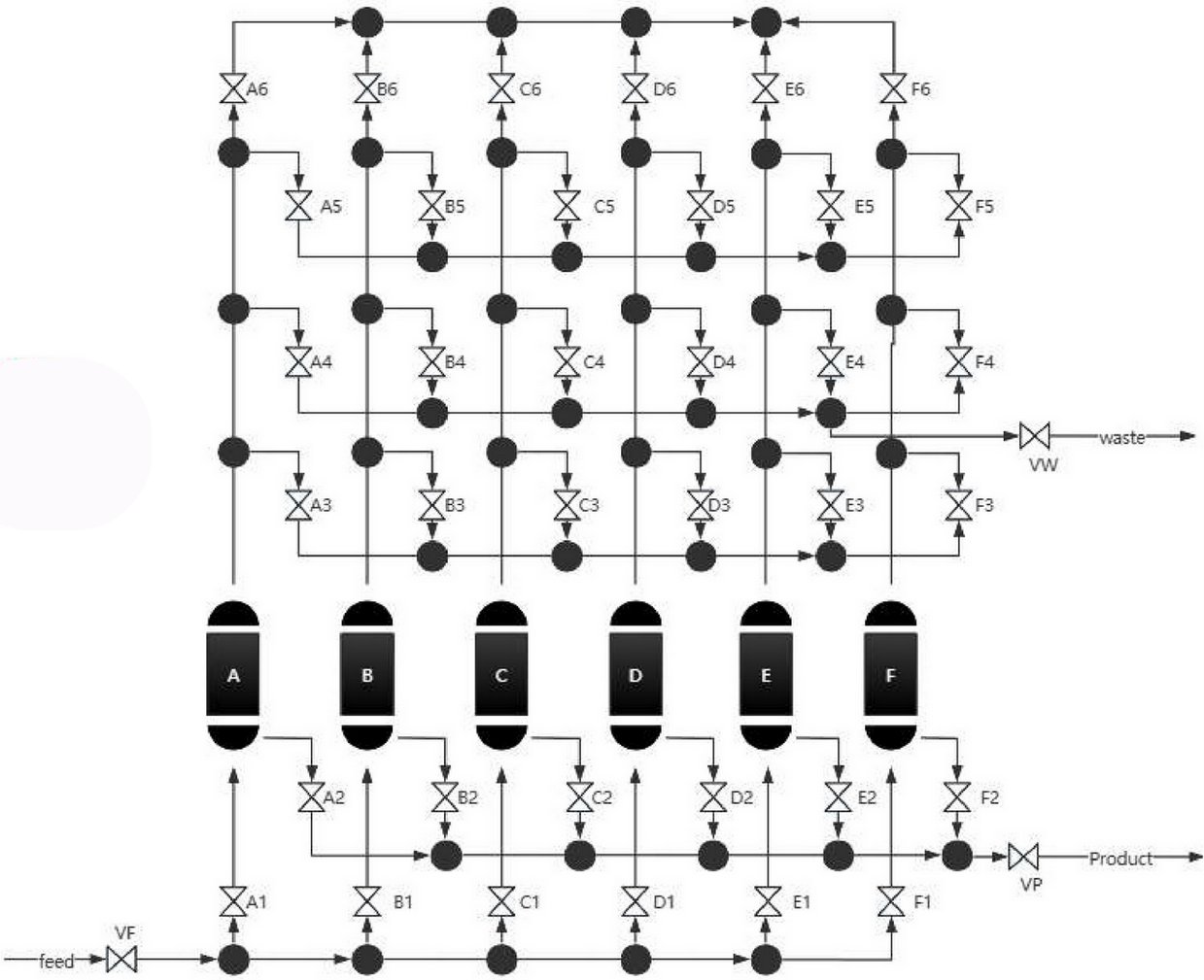

Figure 7 — Schematic diagram of a six-bed PSA process [24]

Multi-layered adsorbent beds using different materials in sequential layers optimize separation performance by removing different impurities in stages.

Applications

- Hydrogen purification: Producing 99.9-99.999+% purity hydrogen from steam methane reforming and refinery streams, removing CO, CO2, CH4, N2, and water

- Nitrogen generation: Separating nitrogen from compressed air at 95-99.999% purity using carbon molecular sieves for oil and gas, food packaging, electronics, and chemical manufacturing

- Natural gas sweetening: Removing CO2 and H2S to meet pipeline specifications

- Blast furnace gas recovery: Separating hydrogen and nitrogen from steel industry off-gases

Advantages and Limitations

PSA prevents adsorbent overheating that can cause feed stream component decomposition and adsorbent poisoning, a significant advantage over TSA. The technology operates at near-ambient temperatures, avoiding thermal degradation issues. However, high energy requirements for feed gas compression represent significant operational costs, particularly for lower concentration feed streams. Physical footprint can be substantially larger than alternative separation technologies.

Vacuum Pressure Swing Adsorption (VPSA)

VPSA combines principles of PSA with vacuum regeneration, performing adsorption at atmospheric or slightly elevated pressure and regenerating by applying vacuum (0.1-0.2 bar absolute). This configuration eliminates expensive feed gas compression while achieving effective regeneration.

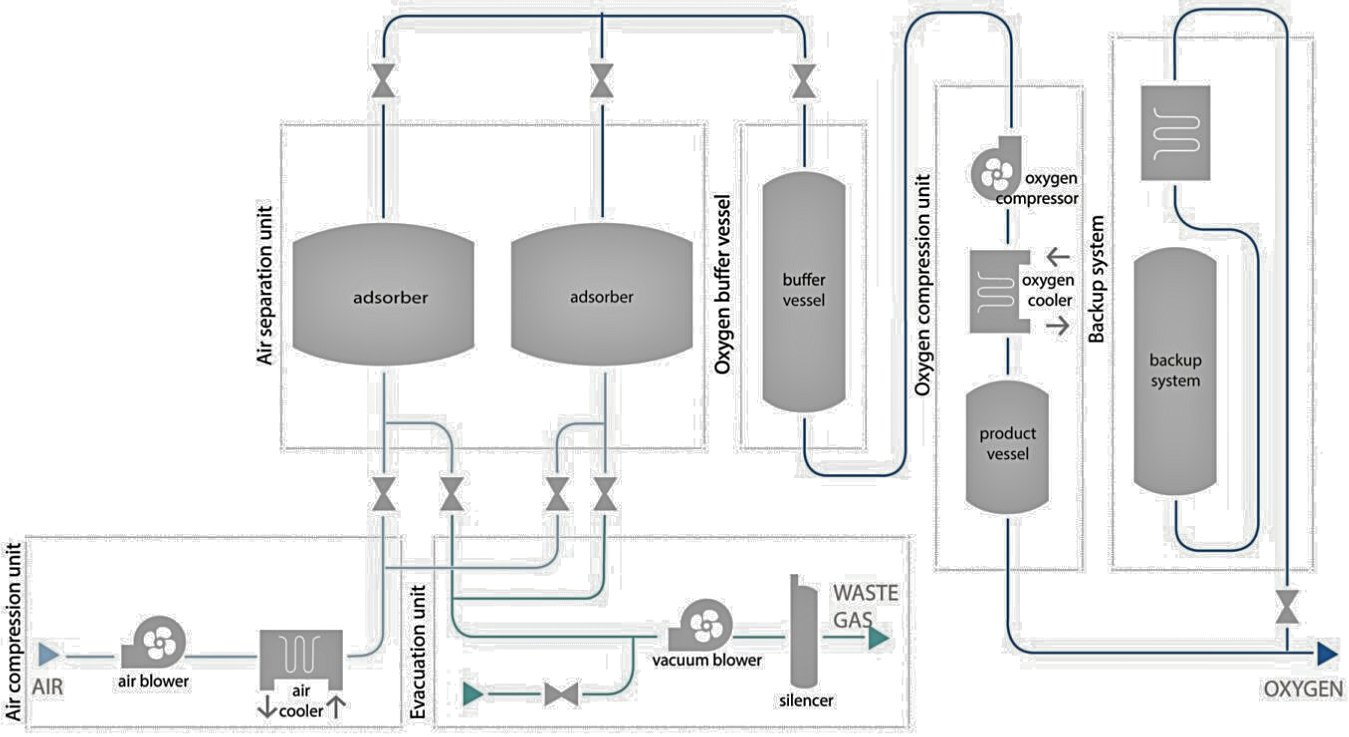

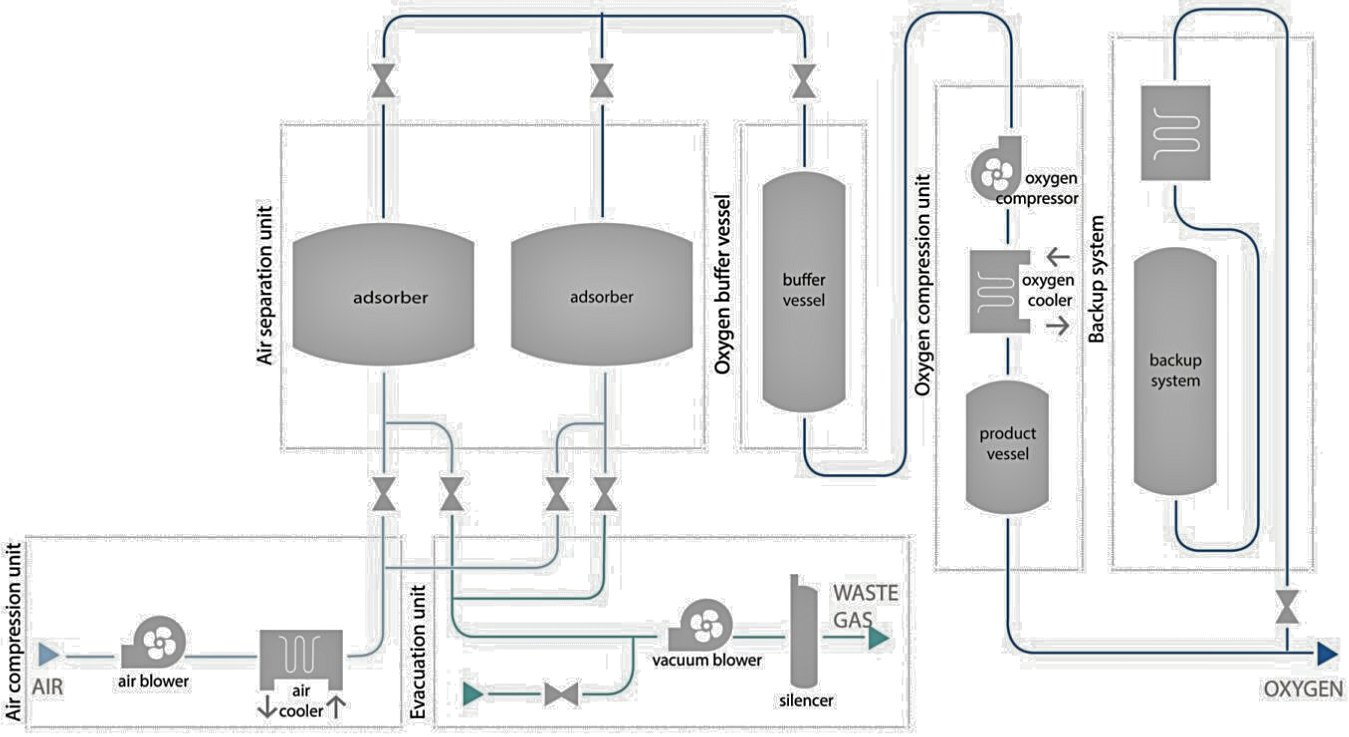

Figure 8 — Mahler AGS Oxygen VPSA Flow Sheet [34]

Process Configuration

VPSA systems typically employ 4-6 step cycles including pressurization, adsorption, blowdown, evacuation, and purging. Multiple beds operate simultaneously under PLC control with program-controlled valves ensuring continuous product delivery.

The key distinction from conventional PSA is that adsorption occurs at atmospheric pressure with desorption under vacuum, whereas typical PSA units perform adsorption at elevated pressure with desorption at atmospheric pressure.

Applications

- Oxygen production: The standard technology for on-site oxygen generation from air at 90-95% purity using zeolite 13X molecular sieves for steel, metallurgy, wastewater treatment, healthcare, aquaculture, and chemical oxidation

- Industrial gas separation: Iron and steel blast furnace off-gases, petrochemical operations, and natural gas sweetening

- Biogas upgrading: Concentrating methane by removing CO2 and other components

Advantages and Limitations

VPSA eliminates high-pressure feed gas compression, reducing both capital and operating costs compared to conventional PSA for atmospheric pressure feed streams. The technology is more energy-efficient than cryogenic air separation for oxygen production capacities below approximately 10,000 Nm³/h. Vacuum pumps add equipment complexity and maintenance requirements but generally consume less energy than compressing large volumes of feed gas.

Comparative Overview

| Parameter |

TSA |

PSA |

VPSA |

| Regeneration method |

Temperature increase

130-150°C+ |

Pressure reduction

to atmospheric |

Vacuum application 0.1-0.2 bar |

Cycle

time |

Minutes

to hours |

Seconds

to minutes |

Seconds

to minutes |

| Feed conditions |

Ambient pressure and temperature |

High pressure

>8 bar |

Atmospheric

pressure |

Energy

source |

Steam/thermal

fluid + electricity |

Electricity for compression |

Electricity for

vacuum pumps |

Bed

utilization |

Maximum capacity utilization |

Moderate capacity utilization |

Moderate capacity utilization |

| Typical configuration |

2-3 beds |

2-16 beds with pressure equalization |

2-6 beds |

Key

advantage |

Complete contaminant removal |

Avoids thermal degradation |

No high-pressure compression |

| Primary limitation |

Long cycle time, large beds |

High compression energy |

Vacuum pump complexity |

| Commercial maturity |

Proven commercial technology |

Widely deployed, mature technology |

Oxygen: Commercial

Others: emerging |

References

- Pearson C., APEX Gas Generators. Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) Technology – How It Works (May 31, 2025)

- VITO (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Temperature Swing Adsorption. EMIS MAP-IT CCU Technologies Database

- VITO (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Pressure Swing Adsorption. EMIS MAP-IT CCU Technologies Database

- ZEOCHEM (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). PSA Hydrogen Purification. Applications Guide

- Atlas Copco (Apr 17, 2025). How a PSA Nitrogen Generator Works. Air Compressor Blog

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Last updated: Jun 24, 2025). Desiccant Dehydrators. Natural Gas STAR Program

- ZEOCHEM (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Molecular Sieves. Products Catalog

- AGCET (2024). Study on the Adsorption Performance of Zeolite Molecular Sieves. Semantic Scholar PDF.

- ScienceDirect Topics (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Adsorbent Material - An Overview. Engineering Topics

- BENONI Technologies (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). What Are the Main Types of Adsorbents? How About Their Typical Applications?

- AIChE (Aug 2017). Adsorption Basics: Part 2. Technical Document

- DEC Group (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Molecular Sieves MZA™ - Zeolite Solutions

- BERG Kompressoren (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Adsorption Material & Molecular Sieves

- Luna-Triguero, A. (Jun 2019). Molecular Simulation on the Adsorption of Olefins and Paraffins in Nanoporous Materials. PhD Thesis, Universidad Pablo de Olavide

- Science Advances (Jul 2025). Tandem Reaction-Adsorption Separation of Perfluorinated Compounds. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adt9498

- Arkema (May 2012). Molecular Sieves: Contaminants, Effects, Consequences and Mitigation. Technical Data Manual

- Energy Fuels (Aug 2017), 31, 9, 9760-9775. Evaluating the Feasibility of a TSA Process Based on Steam Regeneration. DOI: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b01508

- ProGas LLC (Jul 2025). What's Changed in Natural Gas Dehydrators

- Dwyer Instruments, LLC. An Insight into Gas Generation Industry

- ZEOCHEM (Mar 2019). PSA vs TSA: What's the Difference? Technical News Article

- Toyo Engineering (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Pressure Swing Adsorption Unit (PSAU)

- AIChE Journal (Aug 2024). A Numerical Comparison of Heavy-Purge and Dual-Reflux Strategies. DOI: 10.1002/aic.18573

- Separation Processes (n.d.). Adsorption - Chapter 2. Online Textbook

- ScienceDirect (Dec 2025). Optimization and Comparison of Multi-Beds PSA Systems. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccst.2025.100035X

- ACS Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research (Apr 2009). Optimization of Multibed Pressure Swing Adsorption Processes. DOI: 10.1021/ie801357a

- Farooq, S. (Jan 2011). Cycle Scheduling and Design of Pressure Swing Adsorption Systems. PhD Dissertation, University of South Carolina

- World patent WO2005115590A1 (May 2018). Continuous Feed Three-Bed Pressure Swing Adsorption System

- Skoge, S. et al. (2017). Modelling and Simulation of Multi-Bed Pressure Swing Adsorption. ESCAPE17 Conference Proceedings

- Generon (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Hydrogen Recovery Packages. Product Literature

- BERG GaseTech (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). PSA Nitrogen Generators for the Oil and Gas Industry

- VPSA Gas (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Vacuum Pressure Swing Adsorption Oxygen Plant (VPSA-O2)

- Universitat Abat Oliba (May 2023). Parameter Screening of a VPSA Cycle with Automated Breakthrough Detection

- Atlas Copco (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). OGV+ VPSA Oxygen Generators

- MAHLER AGS (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). Efficient VPSA Oxygen Plants

- Atlas Copco (accessed: Jan 17, 2026). How is Industrial Oxygen Produced?

- Bangwin Gas (Mar 2024). Pressure Swing Adsorption vs Temperature Swing Adsorption - Molecular Sieve Purification Process

- Molecular Sieve Desiccants (Nov 2025). Silica Gel vs Zeolite Molecular Sieve: An Overview

- ACS Langmuir (Feb 2024). Adsorption Isotherms and Breakthrough Curve Analysis. DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c03075

- TU Delft Repository (2019). Prediction of Adsorption Isotherms from Breakthrough Curves

- Imperial College London (Nov 2011). Model-Based Design, Operation and Control of Pressure Swing Adsorption. Spiral Repository